The Black Hills

South Dakota

May 2015

Our favorite local character and fellow diner back at The Hill City Cafe…

…recommended that we not miss Crazy Horse. Sage advice, that. So there is Crazy Horse, the man and Crazy Horse, the mountain carving.

Crazy Horse, the man

Crazy Horse was born of parents from different tribes. He was a baby at the time. Mom was a Miniconjou and Dad, Oglala. The child was given two names. One was Čháŋ Óhaŋ meaning “Among the Trees.” The other was Cha-O-Ha meaning “In the Wilderness.” It kind of depends on which orthography you use. Both names suggest someone at one with nature.

“Crazy Horse?” In the Lakota language, Thasuka Witko, literally meaning “His-Horse-is-Crazy.”

Everyone called him Curly. Really. However, once he proved himself in combat, he became worthy to take his father’s name which was Tȟašúŋke Witkó, or Crazy Horse. Junior is the Crazy Horse we know.

Young Crazy Horse — they could have called him “Crazy Colt,” but they didn’t — young Crazy Horse grew up to become a warrior and leader of the Lakota Sioux, and fought for the preservation of his Native American traditions and way of life. The U S government made treaties with the Sioux but apparently never really intended to honor those agreements. They soon tricked the Natives, attempting to herd them onto reservations. Crazy Horse fought alongside Sitting Bull in the American-Indian Wars, and led the resistance against the enforced internment of the Sioux onto the reservations.

In the Great Sioux War of 1876, Crazy Horse led a combined army of Lakota and Cheyenne in an attack against General George Crook, preventing Crook’s forces from joining up with General Custer, thus setting the stage for the eventual defeat of Custer at the Battle of Little Bighorn. Often referred to as “Custer’s Last Stand,” white folks considered it to be one of the worst disasters in the history of our country. For the people who had already been living here, our Native Americans, it was a resounding victory against the invaders.

As time went on, the continued and vastly renewable campaign against the Native Americans eventually wore them down. The advancing armies destroyed buffalo herds, conducted raids on Indian settlements, continued intense and constant harassment and decimated crops and fields. The Sioux could no longer stand up to the white man’s invasions.

After one particular skirmish where several Natives were shot dead, Crazy Horse retreated. With the challenges of a harsh winter ahead, he negotiated an agreement where the starving Sioux would be placed in their own reservation in exchange for their surrender.

For four months Crazy Horse waited the assignment to a reservation that had been promised him. Tensions rose between the nations due to many assumptions, misunderstandings, prejudice and subterfuge. During this waiting period, Mr Horse’s wife Black Shawl fell ill. Without authorization, he took her to her parents for recuperation. Based on this journey, rumors spread that Crazy was planning a rebellion so he was swiftly arrested by forty government scouts. Forty! At first, he offered no resistance. But then realizing that he had been betrayed and was being led to a holding cell, he began to struggle. While one of the arresting officers pinned his arms, another soldier ran him through with a bayonet. The jagoffs. He died later that night. He was 36 years old.

I salute the light within your eyes where the whole universe dwells. For when you are at that center within you and I am at that place within me, we shall be one.

— Crazy Horse, smoking the Sacred Pipe with Sitting Bull

Crazy Horse, the mountain

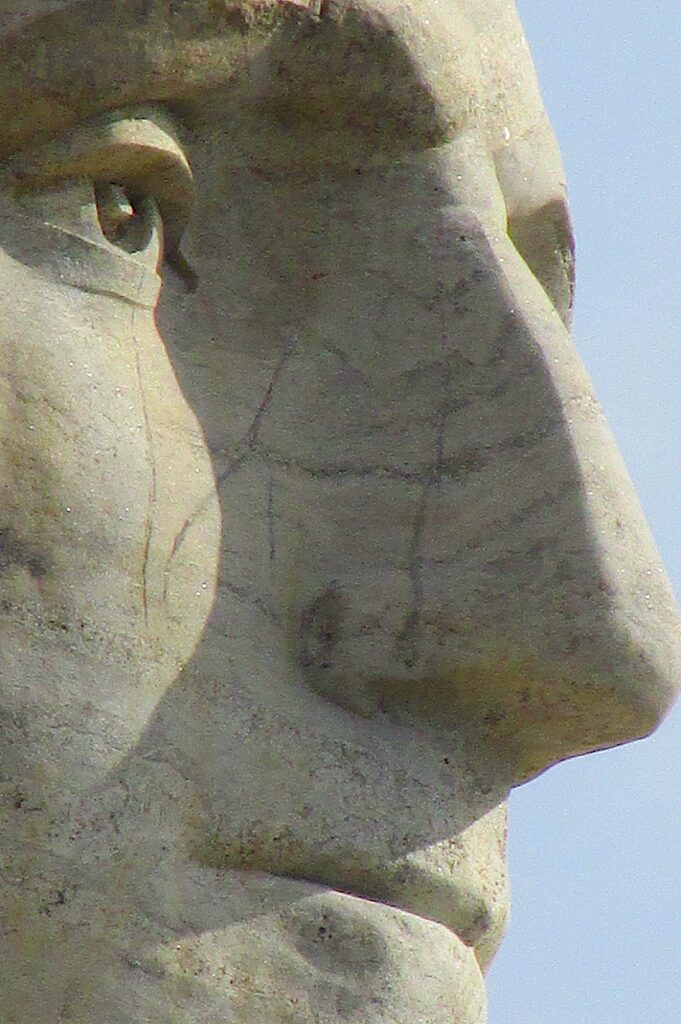

The Lakota tribes recognized Crazy Horse as a visionary leader committed to preserving the traditions and values of the Lakota way of life. For this, and for his ferocity in battle, his dedication to his tribe’s heritage and for his cunning and leadership, a monument arose. Or rather, a monument is arising.

There is a rumor that when Crazy Horse died, he uttered the promise, “I will come back in stone.” Prescient and tantalizing, or even mystical as this may be, it’s likely that he never actually said these words. And yet…

James H Cook was a cowboy, hunting guide, explorer and fossil collector, an amateur historian, author and friend of Red Cloud, the prominent Oglala Lakota leader. He also engaged in many other progressive and exciting ventures leading to such honors as having his collection of fossils displayed in the Agate Fossil Beds National Monument in Nebraska. He took an interest in the history and culture of the region’s Lakota peoples and wrote two books about life on the frontier. Cook was elected to the National Cowboy Hall of Fame.

In 1933, Cook hatched the idea of building a monument to Crazy Horse at Fort Robinson, the location in Nebraska where Mr Horse was killed. Crazy Horse’s maternal cousin, Henry Standing Bear, himself an Oglala Lakota chief, caught wind of this memorial and convinced Cook and everyone else that a monument should be built, yes, but in the culturally and spiritually appropriate Paha Sapa, the Black Hills of South Dakota, the land of the Lakota.

Standing Bear sought out a suitable sculptor.

Meanwhile, to the east 8.7 miles as the crow flies or 16.1 miles as the crow drives, Gutzon Borglum was busy building a monument to some white presidents, and thereby, to America.

Before that however, Borglum was the designer of the Confederate Memorial Carving at Stone Mountain, Georgia, the largest bas-relief sculpture in the world. That jolly racist organization, the Ku Klux Klan, provided major financing for the sculpture, which depicted three Confederate leaders of the Civil War: Jefferson Davis, Robert E Lee and Stonewall Jackson. Borglum was sympathetic to their white supremacist philosophy. The jagoff.

He was also quite a bull-headed authoritarian and after a few arguments, Borglum smashed his model of the sculpture and packed up his things and left, Black Hills-bound. In his wake, the incomplete mountain sculpture was smoothed over and the group started once again with a blank slate.

Gutzon Borglum’s next assignment was to carve up a mountain in the Black Hills, depicting the heads of four presidents: George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Teddy Roosevelt and Abraham Lincoln. The mountain was called Six Grandfathers by the Natives. The white people had no name for the place until they began to carve it up.

Sculpting the faces into this granite mountainside was a complicated process. Four hundred miners, some swinging around in bosun’s chairs, worked for 14 years beginning in 1927. The price tag was almost a million dollars (18 million in 2019 dollars.) The rock required a great amount of dynamite and political finagling to turn it into heads. During the 14 years, Borglum hired one artist to assist the process. That artist was Korczak Ziolkowski. He lasted nineteen days when a heated argument with Borglum’s son chased him away.

Henry Standing Bear had heard of Korczak Ziolkowski, who had just won a big deal prize at the New York World’s Fair. So he hired him to create this mountain tribute to the North American Indians. Korczak was now Black Hills-bound.

Henry Standing Bear, aka Mato Naji, was the Oglala Lakota chief who commissioned Ziolkowski to build the memorial. To kick things off, Ziolkowski shared his message of hope that the memorial would serve to create cross-cultural understanding and mend relations between Natives and non-natives. He wrote, “My fellow chiefs and I would like the white man to know the red man has great heroes too.”

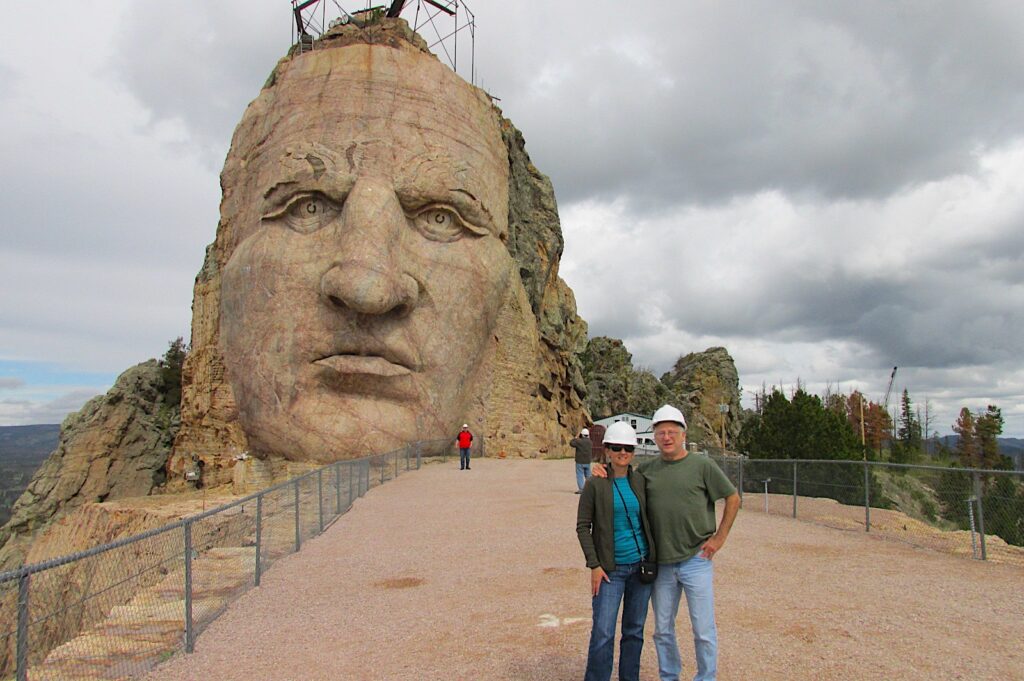

Not good, not bad, but probably not the best approach for mending relations. Especially when we consider how clever Mato Naji was when the design of the Crazy Horse Memorial called for a figure ten times as tall as the Mount Rushmore carvings. In fact, it is the world’s largest mountain sculpture in progress. Just how big is it?

. The hand will be about 25 feet tall.

. The pointing index finger will be almost 30 feet long.

. The horse’s head will be 219 feet tall. The Statue of Liberty, from heel to crown, is just over 111 feet tall. The Rushmore presidents’ heads are 60 feet tall.

When finished, as a symbol of pride, courage and strength, the stone Crazy Horse will look over the Black Hills, land of his Lakota peoples.

The carving itself will command the terrain for hundreds of miles. It will be a likeness based on oral history, because Crazy Horse never allowed himself to be photographed. We are building a statue of this guy, with a head as high as three buses long, twelve times as tall as André the Giant, as high as an eight-story building, and we don’t even know what he really looked like!

Korczak Ziolkowski and his wife Ruth had 10 children. Four of the kids and many of the 23 grandchildren still work on the project. They’ve been at it since 1948. Ask them what the expected completion date is and they will tell you, “We’re not exactly sure.” They have no idea.

Korczak was singleminded about progress on the sculpture, focused on the future. The completion will not be until long after his death in 1982.

One story has it that, while moving some of the earth on the carving, Korczak’s son drove a tractor a bit too close to the edge and it toppled over. He managed to jump out before getting crushed under when it hit the ground. Korczak looked up from his work at the commotion, his hammer briefly still. Once he saw that his son hadn’t been injured, he is rumored to have said, “You got it in, you get it out.” And then he went right back to his chiseling.

Let’s be clear. Not everyone shared Mato Naji’s vision of the appropriateness of this representation. In short…

One descendant took issue with Standing Bear acting unilaterally when Lakota culture dictates consensus. Another wondered about the millions of dollars generated in his ancestor’s name. A Lakota medicine man said, “The whole idea of making a beautiful wild mountain into a statue of him is a pollution of the landscape. It is against the spirit of Crazy Horse,” while another called it, “…an insult to our entire being.”

Nonetheless, it’s going up.

Let us briefly talk about John.

John left Alabama with the intention of getting to Mexico but, as he says, “I guess I made a wrong turn,” and ended up in South Dakota. He had heard about the Crazy Horse sculpture so he decided to visit the monument. “They asked me to fill out an application to work here and the next day they hired me. That was seven years ago.”

As Lisa and I have traveled the country on our High Points mission, we have learned of appalling white people behavior. There is a lot for non-white people to be angry about.

John is our driver here at the sculpture, taking us and a handful of other visitors up the winding dirt road in a van, to stand on the unfinished stone arm of Crazy Horse. John, a full blood Cherokee, is willing to share his perspective of the Crazy Horse story and some of the atrocities visited upon his people.

Depending who you are, the carving at Mount Rushmore might be an inspiring icon honoring the American dream. Or if your skin shade is a bit darker, it might be a symbol of an aggressor’s effrontery, out and out racism.

Think about this. This proud monument, Mount Rushmore, commemorating heroes of white American supremacy has been built on land acquired through lies, violence and trickery.

John is willing to tell us aspects of the story that are hard to find in the history books. What is amazing to me is that with all the unfair, ghastly treatment the white guys doled out to the red guys, John does not sound bitter or angry. He acknowledges the atrocities, but he looks forward. Y’know, this happened, that happened, but here we are and here is where we want to go.

I have a lot to learn from John.